Scalar and Vector Fields

Prerequisites: To get the most out of this web page you should know about:

- Functions and functional notation

- Vectors, including the dot product and the cross product.

- Single variable calculus (basic differentiation, indefinite integration, and definite integration).

Contents of this page:

Definition: A field is a physical quantity that has a value at every point

in some region. The region might be a region of 3-dimensional space, or it might be a surface

or a curve. The physical quantity could be a scalar (in which case we have a

scalar field) or a vector (in which case we have a vector field).

For example the temperature throughout a room is a scalar field in 3-dimensions. The temperature along a wire in a toaster is a scalar field in 1-dimension. In a weather forecast, the wind velocity over a country is a vector field in 2-dimensions. The vector at any point represents the wind speed and direction at that point. The field could be static (not changing with time) or it could be dynamic (time-dependent).

The pictures below show some examples of fields.

Example of a scalar field. The physical quantity is the overnight low temperature in °F (32°F is freezing), and the region is the USA. This field changes daily. Click here to see the frost forecast for tonight.

In this first picture we show a temperature field. The region is part of the earth's surface centered on the USA. The physical quantity is the lowest temperature that is expected overnight. This field is of great interest to farmers and fruit growers because frost and freezing temperatures will ruin their crops.

The field is described using numbers and colors. The numbers are temperatures in °F. The turquoise colored band indicates temperatures right around the freezing point, 32°F, so frost is expected. The blue and purple areas have temperatures far below freezing.

This is a 2-dimensional scalar field because the earth's surface is 2-dimensional and because temperature is a scalar. It is dynamic because it changes every day.

Example of a vector field. The physical quantity is the wind velocity and the region is the west coast of North America. This field also changes with time. Click here to see the wind forecast for today.

This picture shows a wind velocity field. The region is the west coast of North America around Vancouver where I live and the physical quantity is the wind velocity. This field is of interest to sailors and fishermen.

To help visualize this field the picture uses arrows and colors. The arrows point in the direction of the wind and their lengths are proportional to the wind speed (the magnitude of the velocity). The red regions have the highest wind speeds and the blue regions have the lowest speeds.

This is a vector field because velocity is a vector.

The electric field around a + and − electric charge pair (called a dipole). Click here to go to the PhET simulation where you can drag these charges around yourself and see how the field changes.

This picture shows the electric field around a + and − electric charge pair (called a dipole). The electric field is the force that a tiny, positive, unit "test" charge would feel if it was placed at any location. Since like charges repel and opposite charges attract the field lines come out of the + charge and go into the − charge.

As long as these charges don't move the field is static. To help visualize this field the picture uses arrows of varying brightness. The arrows point in the direction of the electric field and the brighter they are, the stronger the field.

Note that electric fields are actually 3-dimensional. They come out of the + charge and go into the − charge uniformly in all directions. For simplicity, though, the picture shows only the field vectors in the plane of the screen.

The magnetic field around a current-carrying solenoid. In the photograph, the field is made visible by sprinkling iron filings on a plexiglass sheet.

This pair of pictures shows the magnetic field in a 3-dimensional region around a coil of wire (called a solenoid) that is carrying an electric current. The magnetic field shows the direction in which the north pole of a compass would point if it was placed at any location.

In the drawing on the left, many tiny vector arrows have been joined end-to-end to form continuous curves called field lines.

In the photograph on the right, iron filings have been sprinkled on a sheet of plexiglass. They become magnetized and these tiny iron magnets link up end-to-end to create lines. Magnetic fields are also 3-dimensional vector fields, but they are very different from electric fields in that there are no sources or sinks – instead the field lines form closed loops.

To denote a scalar field like the temperature field in 2 dimensions (described above) we can generalize ordinary function notation: Let x and y together specify a location in the region and let s be the scalar field's value at that location. Let f be a function that takes both x and y as input and gives s as output:

For example suppose that

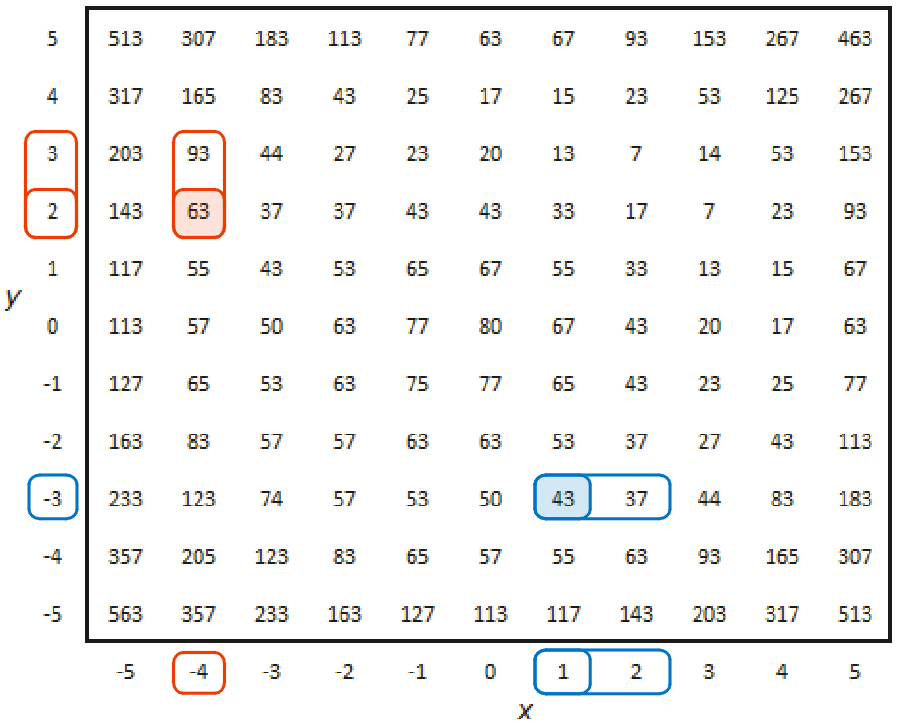

The function f (x,y) displayed as a simple grid of values.

Then evaluating f at a grid of locations gives the scalar field shown to the right.

For example, f (0,0) = 80 and f (3,0) = 20 meaning that s = 80 and s = 20 at those locations, as indicated by the circles.

A contour map of the same field. The Algebra Coach app was used to make this map.

The same field is much easier to visualize if we draw a contour map of it. A contour map displays a set of level lines (lines along which the scalar field s is constant). For example everywhere on the outside ring s = 70.

A 3D projection of the same field. Maple was used to make this picture and the axes can be rotated to view the surface in any orientation.

Another way to visualize the scalar field is to plot s in the z direction. This is called a 3D projection.

A 3D projection makes hills and valleys easier to recognize but a contour map makes numerical values easier to find.

If the scalar field is in a 3-dimensional region then we simply include a z coordinate in the function f and if it depends on time then we include a t coordinate, like this:

A vector may be denoted in any of 3 ways:

- by name, using a bold-face letter. e.g. ... the vector v ...

- by components, using an ordered pair or triple. e.g. ... v = (3, 4 −5) ...

- by linear combination of the unit vectors î, ĵ,

.

e.g. ... v = 3 î + 4 ĵ −5

.

e.g. ... v = 3 î + 4 ĵ −5

If anything in this list is unfamiliar, refer to the vectors chapter of my book.

To denote a 2-dimensional vector field like the

wind velocity field above

we can, as before, let x and y specify a location in the region.

But this time we want there to be a vector v at that location.

Since v has 2 components we need 2 functions,

one to output the x component of v (call that function vx),

and another function to output the y component (call it vy):

The notation v (a, b) = (c, d) means that at position (a, b) the field vector is (c, d).

Thus we will use the following ‘function’ notation to describe a vector field.

A location (x, y) goes into the function machine and a vector (vx, vy)

comes out:

Important note: Look at the picture to the right. The position (a, b) can be thought of as a vector as well. Then it is called a position vector. But remember that (a, b) is position with units of, say, kilometers and (c, d) is, say, wind velocity with units of knots. Thus we cannot, for example, add these vectors.

To become more familiar with the notation let's look at four examples.

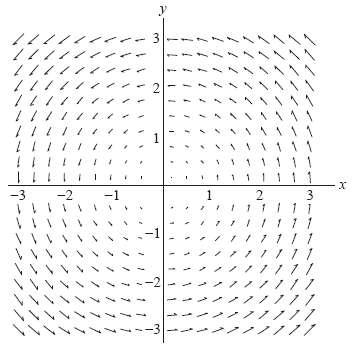

The vector field v (x, y) = (x, y).

Example 1: v (x, y) = (x, y)

Suppose that x = 1 and y = 2. Then the notation v (1, 2) = (1, 2) means that at the position (1, 2) the field is the vector (1, 2). If v represents wind velocity then the wind is to the right and upward at that point.

Because the field vectors equal the position vectors, the arrows point radially outward. Furthermore the farther from the origin, the longer the arrows. This velocity field could describe an explosion at the origin.

The picture was made using the Maple command:

> plots[fieldplot] ([x, y], x = −3..3, y = −3..3);

Maple scales the lengths of all the field arrows so that the longest one just fits inside one of the 400 grid cells.

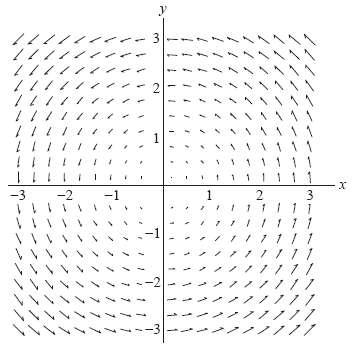

The vector field v (x, y) = (−x, y).

Example 2: v (x, y) = (−x, y)

Again suppose that x = 1 and y = 2. Then v (1, 2) = (−1, 2) means that at the position (1, 2) the velocity is the vector (−1, 2), meaning to the left and up. This velocity field could describe the meeting and deflection of two opposing jets of water.

The vector field v (x, y) = ω (−y, x).

Example 3: v (x, y) = ω (−y, x),

where ω is a positive constant.

Note that the left-hand-side of this field formula is functional notation saying that vector v varies with location, x and y. The right-hand-side gives details for calculating the field vectors. What you see there is not functional notation. It is just ω factored out. It could also have been written as (−ωy, ωx).

If v is velocity then this field could describe a fluid rotating uniformly about the origin with angular velocity ω. (Uniform rotation means that all the particles in the fluid have the same angular velocity.) Click here for more information on uniform circular motion.

To prove that the field describes rotation about the origin, note that the dot product of the position vector (x, y) and the field vector ω (−y, x) is zero, meaning that they are perpendicular. Since the position vector is radial this means that the field vector must be azimuthal (point around a circle).

To prove that the rotation is uniform, take the dot product of the field equation v = ω (−y, x) with itself.

Letting v and r denote the lengths of the velocity and position vectors and taking the square root gives

This equation implies that the angular velocity is ω at all locations, hence the rotation is uniform.

Putting the − sign on the first component of the field vector causes the rotation to be counter-clockwise. Putting the − sign to the other component would result in clockwise rotation.

Example 4: v (x, y, z) = ω (−y, x, 0), where ω is any positive constant.

On the left-hand-side of this field formula we see that v is a function of x, y and z so this field is 3-dimensional. To graph the field we must add a z axis coming out of the screen.

On the right side are the formulas for the three components of the field vectors. Let's assume, as in Example 3, that v describes the velocity field of a fluid. Note the following:

- The z component of v is zero. This means that there is no fluid motion into or out of the screen.

- The x and y components of v do not depend on z. This means that the field vectors are the same for every ‘layer’ of z.

- In fact the x and y components of v are the same as for Example 3 so every layer of the fluid has the same uniform rotation that is shown in the picture in Example 3.

It is very useful to express the field formula in terms of the vector cross product. (Note that the cross product is defined only for vectors in 3 dimensions.) Here are the steps:

The first vector in the cross product, ω = (0, 0, ω), is called the angular velocity vector. Its direction is the axis of rotation and its magnitude is the angular velocity. The second vector, r = (x, y, z), is just the position vector. Thus we can write the vector field as

The vector ω is the axis of rotation. The cross product ω x r describes uniform rotation about this axis.

The nice thing about this vector formula is that it automatically gives the correct direction for the velocity field (because of the right-hand-rule of the cross product).

The field equation v = ω x r describes uniform rotation about any axis of rotation.

Also it is easy to describe uniform rotation about any axis. For example if we want to know the vector field for uniform rotation with angular velocity 2 radians/sec about the axis (3, 4, 5) then we set up this ω vector:

and express the vector field as v = ω x r where ω = (0.85, 1.18, 1.41) and r = (x, y, z).

Previously, we looked at a scalar field described by the formula

Remember that the left side of the formula says that the field s depends on the location (x, y). The right side says how to calculate the field. We displayed the field using a grid of numbers (which we have duplicated below) and we also saw a contour map and a 3D projection of the field.

In this section we want look at the rate of change of the field as we move in various directions.

Approximating the partial derivatives. Using the numbers in the blue boxes approximates ∂s/∂x at the point (1,−3). Using the numbers in the red boxes approximates ∂s/∂y at the point (−4, 2)

Suppose that the field s represents elevation in meters and that the x and y components of the location are measured in kilometers. Then the elevation at the point (1, −3) (the blue point) is 43m. If we move 1km in the x direction then the elevation is 37m. Thus the elevation is decreasing at a rate of approximately 6m for every kilometer. If we want more accuracy then we need to use a finer grid.

We can generalize the ordinary derivative of single variable calculus and define the partial derivative of s in the x direction to describe this.

Thus in the grid shown, h=1, and the notation “lim h→0” means “make the grid finer and finer”.

The same goes for the y direction. The elevation at the point (−4, 2) (the red point) is 63m. If we move 1km in the y direction then the elevation is 93m. Thus the elevation is increasing at a rate of approximately 30m per kilometer. Again, if we want more accuracy then we need a finer grid.

We define the partial derivative of s in the y direction as

These partial derivatives are easy to calculate. To get ∂s/∂x just treat y as a constant and take the derivative with respect to x, as usual. To get ∂s/∂y, treat x as a constant and take the derivative with respect to y. Here they are:

Note that the symbol ∂ (called the partial symbol) is used instead of d to indicate that:

- s depends on more than one variable,

- we need to keep the other variable(s) constant when calculating a partial derivative,

- the "partial" derivatives are contributions to the "whole" derivative.

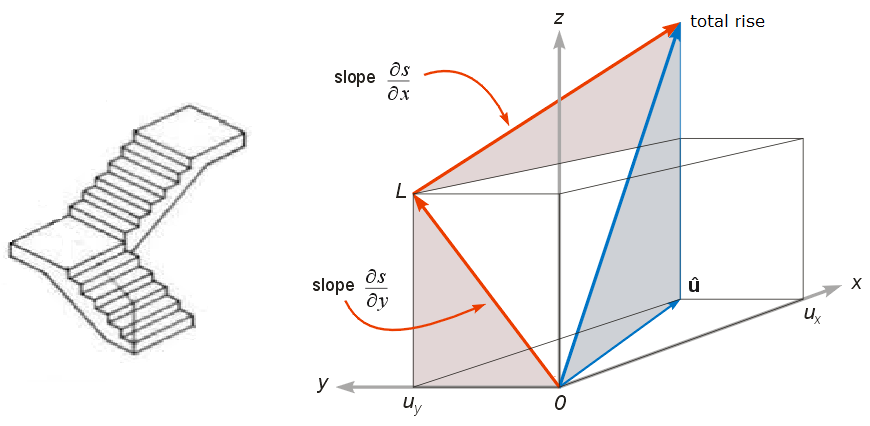

How do we calculate the derivative in an arbitrary direction? To answer this question, look at the pictures below. On the left is a staircase with a flight of stairs, a landing with a 90° turn, and then another flight of stairs. If we know the slopes and the runs of the two flights of stairs, then we can calculate the two rises. Adding them together gives the total rise of the staircase.

In the drawing on the right we use this logic to calculate the total rise as we move from the origin O to the point (ux, uy). The two red arrows represent the two flights of stairs.

(left) Staircase with a 90° turn. (right) Using the staircase as a model we can find the total rise per unit run (i.e. the slope in the direction u).

Multiplying slope × run gives rise, so

The run is given by Pythagoras' theorem

Dividing the total rise by the run gives the derivative of the field s in the direction u:

Notes on this formula:

- On the left-hand-side, Du s is spoken as "the derivative of field s in the direction u".

- We have written the right-hand-side as the dot product of two vectors.

- The first vector is called the gradient of s.

It is denoted ∇s where

is a vector operator called del.

By vector operator we mean that it operates on something (on s) and that

it produces a vector.

Del is a generalization of the ordinary differentiation operator

d/dx.

is a vector operator called del.

By vector operator we mean that it operates on something (on s) and that

it produces a vector.

Del is a generalization of the ordinary differentiation operator

d/dx. - The second vector is a unit vector because it is divided by its own length. We will denote it as û.

- Thus the directional derivative formula can be compactly written as Du s = ∇s·û.

- The dot product has a geometrical interpretation:

∇s·û = |∇s| |û| cos θ = |∇s| cos θ,where θ is the angle between ∇s and û. Since the maximum of the cosine is 1, this means that the maximum possible value of the directional derivative is |∇s|. Furthermore this maximum occurs when θ is zero, which means that the direction in which the derivative is a maximum is the direction of ∇s (that is, ∇s points "straight uphill").

Example: Let's continue with the scalar field

We have already seen a grid of numbers and a contour map for this field and have computed its partial derivatives. Putting the partial derivatives together in a vector gives the gradient,

Let's compute the gradient at a few locations, say at (2, 2) and (−2, 1):

These are the green and red arrows in the plot shown below. We have also used Maple to display the gradient at a grid of locations, using the command:

> plots[fieldplot] ( [4/3*x*(x^2+y^2)-16*x-5, 4/3*y*(x^2+y^2)-16*y-5]);

The contour lines in the background are those of a scalar field. The grid of arrows in the foreground is the gradient of that scalar field. Notice that the gradient is a vector field and that it points in the "uphill" direction of the scalar field (i.e. the direction in which the derivative of the scalar field is the greatest).

Some final notes on the gradient:

- In many problems the negative of the gradient of a scalar field is relevant. For example in the plot above, reversing the direction of all the arrows tells us the direction in which water would flow (i.e. downhill). Another example is heat flow in a conductor. Heat flows from hot to cold, in the direction −∇T, where T is the temperature field.

- In 3-dimensions the del operator is defined as

- Another example: When studying free-falling objects, we have a scalar field called the gravitational potential energy given by the formula PE = m g z, where z is the height. The force of gravity is its negative gradient. It points straight down, toward the ground.

Reminder about the notation v (x, y, z) = (vx, vy, vz) for vector fields:

- The bold-face letter v denotes a vector field.

- v (x, y, z) means that the field's region is 3 dimensional. (x, y, z) is a location in the region.

- v = (vx , vy , vz ) means that the field's vectors have 3 components.

- Each component is a function of the location. For vx , for example, this is denoted as vx (x, y, z).

In the previous section we studied the rate at which a scalar field changes as we move around in the field. We saw that a type of derivative called the gradient is all that we need to calculate the rate of change of the field anywhere and in any direction.

Vector fields can be represented by a grid of arrows, and we now want to describe how the arrows change as we move around in the field. Because the arrows can change in direction and length, this is bound to be more complicated than the scalar case. As we shall see, two types of derivatives are required to calculate the rate of change of a vector field. They are called the divergence and the curl.

The divergence is designed to describe the tendency for vector fields to emanate or diverge out of sources and converge into sinks. (Recall our picture of the electric field.) The curl, on the other hand, is designed to describe the tendency for field lines to form closed loops. (Like in our magnetic field picture.)

The picture below shows four examples of a vector field changing as we move in the x direction. In (a) and (b) the x component of the vectors is slowly increasing (changing from negative to positive). Thus ∂vx /∂x > 0. The divergence contains this term and "sees" this diverging behavior.

In (c) and (d) the y component of the vectors is slowly increasing (changing from negative to positive). Thus ∂vy /∂x > 0. The curl contains this term and sees this rotating behavior.

In (a) and (b) the vector field shows diverging behavior and the partial derivative ∂vx /∂x is positive. In (c) and (d) the vector field shows rotating behavior and the partial derivative ∂vy /∂x is positive.

The divergence can be calculated using the formula

|

|

(1) |

In the next section we will use flux integrals to give a proper definition of divergence (one that does not depend on the xyz coordinate system). In terms of the del operator,

we can express the divergence formula (1) as a dot product.

Notes on the divergence:

- The divergence is a scalar field. (Scalar because of the dot product and field because it exists everywhere in the same region as v.)

- As mentioned in the picture above, the divergence contains the term ∂vx /∂x as well as similar terms for the y and z direction.

- Suppose that v is the velocity field of a fluid (a liquid or gas) and that we have divided the region into many tiny cubic cells. Then the divergence at any location is the rate at which fluid is coming out of that cell. Each term of the divergence is the rate in one of the directions, x, y, z. This exiting of material could be the result of an explosion or of heating a gas.

The curl can be calculated using the formula

|

|

(2) |

In the next section we will use line integrals to give a proper definition of curl (one that does not depend on the xyz coordinate system). Equation (2) can also be expressed in terms of the del operator, this time as a cross product.

Notes on the curl:

- The curl is a vector field because the cross product produces a vector.

- As mentioned in the picture above, the curl contains the term ∂vy /∂x as well as 5 other terms.

- Again suppose that v is the velocity field of a fluid and that we have divided the fluid into many tiny cells. Then the curl at any location describes the rotation of the cell. The magnitude of the curl gives twice the the angular velocity of the rotation and the direction of the curl gives the axis of rotation.

- The curl simplifies greatly if field v has no dependence on z and if the z component of v is zero. Then the curl everywhere points in the z direction. In other words, ∇×v only has a z component, given by

Let's look at the divergence and curl of some of our previous examples. (But we'll have to assume that the fields are 3-dimensional.)

The vector field

v (x, y, z) = (x, y, 0).

∇·v=2 and ∇×v=0 everywhere.

Example 1: v (x, y, z) = (x, y, 0)

The divergence is

The curl is

Note that the divergence is 2 (i.e. non-zero) everywhere, not just at the origin. Thus every point is moving away from every other point. An analogy is blowing up a balloon – every patch of rubber stretches away from every other patch.

(top) The vector field

v (x, y, z) = (−x, y, 0).

∇·v=0 and ∇×v=0 everywhere.

(bottom) The curl is zero, meaning that cells of fluid move along a curve

without rotating.

Example 2: v (x, y, z) = (−x, y, 0)

The divergence is

Thus the field is converging in the x direction but diverging in the y direction for a net divergence of zero. The curl is

If v is the velocity field of a fluid then this means that the cells of fluid are not rotating even though they follow a curved path.

The vector field

v (x, y, z) = (−ωy, ωx, 0).

∇·v=0 and ∇×v=(0,0,2ω) everywhere.

(bottom) The curl is nonzero, meaning that cells of fluid do rotate as they move along a curve.

Example 3: v (x, y, z) = (−ωy, ωx, 0),

where ω is a positive constant.

The divergence is

The curl is

If v is the velocity field of a fluid then this constant curl means that every cell of fluid has the same angular velocity and the same axis of rotation. The angular velocity, ω, is half the magnitude of the curl vector and the axis of rotation is the direction of the curl vector, in this case the z axis.

The electric field around a dipole.

∇·E = ρ/ε0 and ∇×E = 0.

∇·E ≠ 0 only at the charges, meaning that

field lines come out of one charge and go into the other.

As we move away from the dipole ∇·E = 0 implies that the

electric field drops off.

Example 4: The electric field E around an electric dipole.

The divergence of the electric field is

∇·E = ρ/ε0.

This is called Gauss' law (not to be confused with Gauss' theorem, which we will discuss later). ρ is the charge density (charge per unit volume). It is positive at a + charge, negative at a − charge, and zero elsewhere. ε0 is a fundamental constant of nature, called the electric constant. One consequence is that the electric field comes out of the + charge and goes into the − charge. Another is that the electric field falls off as we move away from a charge.

The curl of a (static) electric field: ∇×E = 0.

Michael Faraday discovered that ∇×E = 0 does not hold in a dynamic situation. He discovered that moving a magnet near a loop of wire creates an electric field that causes an electric current to flow in the wire. In general, the curl equation reads:

∇×E = −∂B/∂t.

B is the magnetic field of the magnet. This is called Faraday's law.

The magnetic field around a solenoid.

∇·B = 0 and ∇×B = μ0J.

The white arrows are the current density J and the blue field lines

are the resulting magnetic field B.

Example 5: The magnetic field B near a solenoid.

The divergence of a magnetic field is always zero: ∇·B = 0.

This means that magnetic fields have no sources or sinks. "There are no magnetic monopoles".

The curl of the magnetic field: ∇×B = μ0J.

This is called Ampère's law. J is the current density (electric current per unit area). It is non-zero inside the wire and zero outside it. μ0 is another fundamental constant of nature, called the magnetic constant. One consequence is that the magnetic field forms loops around the wire. As we move away from the solenoid the loops merge and the field decreases in magnitude.

James Clerk Maxwell recognized that Ampère's law only held in steady state conditions and he figured out how to correct it to hold under any conditions. The curl equation then reads:

∇×B = μ0J + ε0 μ0 ∂E/∂t.

The Flux Integral

The flux of field F

through surface S with area A and unit normal

![]() is

F·

is

F·![]() A.

A.

Suppose that F is a constant 3-dimensional vector field and that somewhere

in the field is a plane surface S with area A and unit normal

![]() .

The flux of F through S is defined as the

product of the perpendicular component of F with the area of the surface.

That is,

.

The flux of F through S is defined as the

product of the perpendicular component of F with the area of the surface.

That is,

Notice that the flux is a scalar, and that it is a maximum when F and

![]() are parallel, and zero when they are perpendicular.

are parallel, and zero when they are perpendicular.

What if the surface is curved and/or the field is not constant?

Then to approximate the flux we must break the surface into many tiny elements,

each with its own area ΔA and its own normal

![]() .

Then we must sum up all these flux elements to get the total flux:

.

Then we must sum up all these flux elements to get the total flux:

For more accuracy, we can make the surface elements smaller and smaller. In the limit as they become vanishingly small, this sum becomes a type of surface integral called a flux integral:

Surface integrals are rather complicated to evaluate. If you are interested in the details,

look at this resource

accompanying my book on multivariable calculus. For now, just note that if

(for some reason) the integrand

F·![]() equals 1 then the surface integral just gives the area of the surface.

equals 1 then the surface integral just gives the area of the surface.

If the surface is closed (completely surrounds some region) then the flux integral is denoted like this:

Example: Fluid (liquid or gas) flow. Suppose that a fluid has a velocity field v (with dimensions length/time) and a mass density field ρ (with dimensions mass/volume). (For example, the densities of water, mercury and air at sea level are ρwater=1g/cm3, ρmercury=13.5g/cm3, ρair=0.0012g/cm3. The density of air drops with elevation while the densities of water and mercury are essentially constant.)

The product ρv is called the mass flux. It has dimensions of mass/area/time. It can be interpreted as the mass per unit area and per unit time that crosses an imaginary surface that is perpendicular to v.

ρv is the mass per unit area and per unit time moving in direction v.

The quantity ρv·

![]() dA is the mass per unit time crossing surface element dA.

dA is the mass per unit time crossing surface element dA.

To better understand this, look at the picture, which shows a gray blob of fluid moving through surface element dA in time dt. The length of the blob is v dt and the cross-sectional area is dA, so the volume is v dt dA, and the mass is ρ v dt dA.

If the surface element's normal

![]() and the velocity v are not parallel, then we must include the dot product,

so that now the mass crossing the surface element dA in time dt is

ρv·

and the velocity v are not parallel, then we must include the dot product,

so that now the mass crossing the surface element dA in time dt is

ρv·

![]() dt dA.

dt dA.

If the surface is closed, then integrating over the whole surface and dividing by the time dt gives the rate at which mass is leaving the enclosed region:

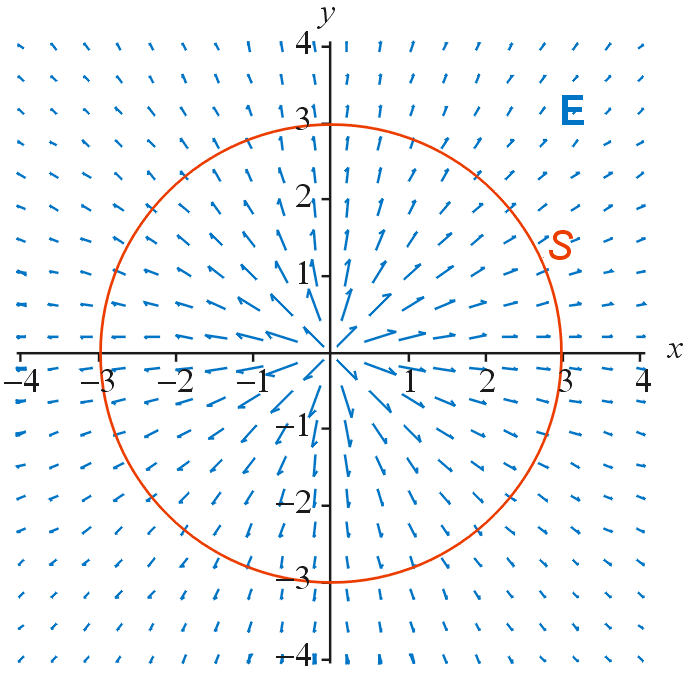

E is the electric field surrounding a + charge placed at the origin. S is a spherical surface centered at the origin. The sphere's surface area is proportional to r 2, where r is its radius, while the field's magnitude drops like 1/r 2. Thus the flux of E through S is constant, independent of radius.

Example: The electric field E around a positive charge q located at the origin is given by the formula

where k is Coulomb's constant, r is the distance from the origin, and

![]() is a unit vector that points radially outward from the origin.

Thus the direction of the field is radially outward and the magnitude drops off with

the distance squared from the charge.

is a unit vector that points radially outward from the origin.

Thus the direction of the field is radially outward and the magnitude drops off with

the distance squared from the charge.

Let's calculate the flux integral of the electric field over a spherical surface S centered at the origin and having radius R.

Substitute in the formula for E. Then use the fact that the electric field is everywhere normal to the surface. Then use the fact that the surface area of a sphere is 4πR2.

Thus we see that the flux is constant, independent of radius. In fact, it is not hard to see that the flux is independent of the shape of the surface, thanks to the inverse square law of the field and the square law of area canceling each other out.

Flux and Divergence

Previously, we gave a formula for the divergence. Now we want to actually define the divergence. This had to wait because the definition requires the concept of flux. Once we have a definition of the divergence we will be able to better understand what divergence is, and we will be able to derive a formula for it in any coordinate system.

Definition: The divergence at a point in a vector field F is defined as the outward flux of the field through the surface S of an infinitesimal volume V containing the point, divided by the volume of V. That is,

|

|

(3) |

Setup to derive the formula for the divergence in rectangular coordinates.

The picture shows the setup to derive the divergence formula, (1), from the definition of divergence, (3). Construct a rectangular solid with dimensions Δx, Δy, and Δz centered on point P. Assume that F varies slowly enough that we can approximate it by its value at the six face centers. The outward flux through the six sides (in the order: front, back, left, right, top, bottom, in the picture) is:

Now evaluate the dot products and divide by the volume.

In the limit of a vanishingly small volume, the right-hand-side becomes the same formula for the divergence, (1), that we stated previously.

The Line Integral

A path C through a vector field F.

Suppose that F is a 3-dimensional vector field and that C is a curve in the field going from point a to point b. Do the following:

- Digitize the curve: choose n points r1, r2, …, rn, along the curve. These are the black dots in the picture.

- Use the difference between the coordinates of one point and the next to construct a list of secant vectors Δr1, Δr2, …, Δrn−1. These are the red arrows.

- At each point (black dot), take the dot product of the field vector (the blue arrow) and the secant vector (the red arrow). For instance at the first point, a, we have the dot product F(r1)·Δr1.

- Sum up all the dot products:

- Let the number n of points on the curve become larger and larger. In the limit as n goes to infinity, the secant vectors become tangent vectors and the sum becomes an integral. We call it the line integral of the field F over the curve C.

If the curve C is closed (i.e. if the curve ends where it starts) then we call the line integral the circulation, and denote it like this:

One of the most important applications of the line integral is to calculate the work done by a force field F on a particle that moves along a curve C.

Calculating the line integral of a vector field over various curves.

Example: The picture shows the field F (x, y, z) = (−ωy, ωx, 0). We will calculate the line integral along the red, green and blue curves. (Assume that all the curves are in the z=0 plane.)

Red curve: This one is easy – no integration is required. Everywhere along the circle the field vectors and the tangent vectors point in the same direction and the field vectors have constant magnitude. This magnitude is ωr, where r is the radius of the circle. The circumference of the circle is 2πr. Multiplying the field's magnitude by the circumference gives the line integral (or circulation) 2ωπr2.

Green curve: This one is almost as easy. The tangent vector dr reduces to (dx, 0, 0). Also everywhere along the curve the value of y is −2, so the line integral is

The solid blue curve: (Ignore the dashed blue segments for now.) For this one we will have to parametrize the curve. The next line shows three things: (1) the parametrization, (2) how it allows us to move along the curve as t ranges from 0 to 1, and (3) how dr/dt is the tangent vector.

The line integral is now calculated by replacing dr in the integral by the product of dr/dt and dt as shown here:

Some final notes:

- The line integrals over the dashed blue curves are both zero because the field vectors and the tangent vectors are perpendicular.

- If we combine the solid blue curve and the two dashed blue curves we get a closed

curve whose combined line integral (circulation) is 9ω+0+0. Notice that this equals

the area of the enclosed triangle, 9/2, multiplied by the curl, 2ω.

(The same goes for the circle. The line integral also equals the area, πr2, multiplied by the curl, 2ω.) This remarkable connection between the curl inside some area and the line integral on its perimeter is the content of Stokes' Theorem, which we look at in the next section. - Reversing the direction of any curve flips the sign of the line integral.

- If we reverse the direction of the two dashed lines then the resulting dashed path has the same start and end points as the solid blue curve, but the line integral is zero. Thus we have an example of a field for which the line integrals are path dependent.

Circulation and Curl

Previously, we gave a formula for the curl. Now we want to actually define the curl. This had to wait because the definition requires the concept of circulation. From the definition of the curl we will be able to better understand the curl and we will be able to derive a formula for it in any coordinate system (rectangular, spherical, cylindrical, etc.)

Definition: The curl at a point in a vector field F is a vector whose length and direction are the magnitude and axis of the maximum circulation. More precisely, suppose that P=(x,y,z) is a point in space and that û is a unit vector pointing in some direction. Construct a plane that contains P and that is normal to û. Let C be a small closed curve in the plane that surrounds P and whose direction is related to the direction of û by the right-hand-rule. Let A be the area inside C. Divide the circulation around the curve by the area inside the curve, and take the limit as the curve becomes vanishingly small. This is defined to be the component of the curl at point P in the direction û:

|

|

(4) |

The three pictures show the setup to derive the three components of the curl formula, (2), from the definition of the curl, (4).

The left, middle, and right pictures are used to calculate the

x, y, and z components of the curl, respectively,

at a point P. The text describes the z component in detail.

The other components are similar.

For example, for the z component (the third picture), construct a plane

through P normal to the z axis and make the curve a rectangle

with dimensions Δx and Δy. The circulation around the

four sides is

(We are assuming that F varies slowly enough that we can approximate it by its value at the four red arrowheads in the picture). Now evaluate the dot products and divide by the area.

In the limit of a vanishingly small curve the right-hand-side becomes the z component of the curl.

The x and y components of the curl are found the same way using the other two pictures. Putting the three components together gives the curl formula, (2), stated previously.

Gauss' Theorem

Intuitively, Gauss' theorem (also known as the Divergence Theorem) states that "the sum of all sources of a vector field in a region gives the net flux out of the region".

More precisely, it states that the volume integral of the divergence of a vector field F over some region R is equal to the flux integral of F outward through the surface S surrounding the region.

|

|

(5) |

For the theorem to hold, the field must be continuous with continuous derivatives throughout R (i.e. continuously differentiable). Gauss' Theorem holds in any number of dimensions. In two dimensions it is equivalent to Green's theorem. In one dimension it is equivalent to integration by parts.

Derivation of Gauss' Theorem

Region R, with surface S, is broken up into tiny rectangular solid elements.

Suppose that we have a vector field F, and that in the field is a region R with surface S. Imagine dividing R into many tiny rectangular solid elements (boxes). Pick any point P in the region. It is inside one of the boxes. The divergence at P is approximately equal to the flux of F out of P's box, divided by the volume of the box, ΔV.

The approximation becomes exact in the limit as the volume of the box surrounding P goes to zero. Now multiply both sides of this equation by ΔV and sum up over all the boxes that make up the region R.

On the right side of the equation, the sum over all the boxes can be replaced by a sum over all the faces of all the boxes.

Now notice that for any two adjacent boxes, the outward flux from one box is the inward flux into the other box through their common face. In other words, the outward flux from one box cancels the outward flux from the other box through their common face. Only the fluxes through the exterior faces (the ones on the surface S) do not cancel. The result is that the right side of the equation reduces to a sum over just the exterior faces.

In the limit as ΔV→0, the sum on the left side of the equation can be replaced by a triple integral over the volume R, and the sum on the right side becomes a flux integral over the surface S. Thus we get Gauss' theorem, namely that

Example: Using Gauss' theorem, many physical laws can be written in both an integral form (where the flux of one quantity through a closed surface is equal to another quantity), and a differential form (where one quantity is the divergence of another). For example, in fluid flow, we saw previously that the rate at which the mass inside a region R is decreasing because of flow through its surface S, is described by the equation

(Recall that v is the velocity field of the fluid and ρ is the density field.) This is a so-called continuity equation, written in integral form. Let's write it in differential form. First, write the right-hand-side in terms of the density.

Next, use Gauss' theorem to convert the left-hand-side into a volume integral as well.

Finally use the fact the the region R is arbitrary, implying that the integrands themselves must be equal at every point in space.

This is the same continuity equation, but now expressed in differential form.

A Model for Gauss' Theorem

This model will help us understand what Gauss' theorem means.

- The model is 2-dimensional.

- Break up the region R into a grid of ‘tiny’ square boxes, each of size Δx = 1 by Δy = 1 (and thus area ΔA = 1), and each with a point at its center.

- Allow Fx and Fy (the components of field F), to take on integer values only. This implies that the flux of F and the divergence of F also take on integer values only.

- Because Gauss' Theorem is concerned with fluxes, we need only look at the values of Fx on the left and right edges of a box, and the values of Fy on the top and bottom edges.

- n arrows pointing to the right at an edge mean that Fx = n there. (Arrows pointing to the left mean that Fx is negative there.)

- Similarly, n arrows pointing up mean that Fy = n there. (Arrows pointing down mean that Fy is negative there.)

- Arrows pointing out of, or into, a box also indicate flux. m arrows pointing out and n arrows pointing in means that the outward flux of that box is m−n.

- The definition of divergence in this model is that the divergence at a point equals the number of arrows pointing out of its box minus the number of arrows pointing in. Write this number in the box. Here are 3 examples where the outward flux of a box is 3 and hence the divergence at the point in the box is 3.

Three examples of boxes where the outward flux, and hence the divergence, is 3.

- n more arrows pointing to the right at the right edge than the left edge indicate that ΔFx /Δx = n.

- Similarly, in the vertical direction: n more arrows pointing up at the top edge than the bottom edge indicate that ΔFy /Δy = n.

- Adding ΔFx /Δx

and ΔFy /Δy

from points 9 and 10 is another (more complicated)

way to compute the divergence.

For example, calculating the divergence this way for the three examples above gives

(since the boxes have size Δx=1 and Δy=1):

- ∇·F = ΔFx + ΔFy = (0−(−1)) + (1−(−1)) = 3

- ∇·F = ΔFx + ΔFy = (0−0) + (3−0) = 3

- ∇·F = ΔFx + ΔFy = (2−(−2)) + (1−2) = 3

- The condition that the field is continuously differentiable implies that the arrows exiting one cell count as arrows entering its adjacent cell.

- Gauss' theorem in this model states that the sum of all the numbers in the boxes (representing the volume integral of the divergence in the region) equals the sum of all the arrows on the perimeter of the region (representing the flux integral on the surface).

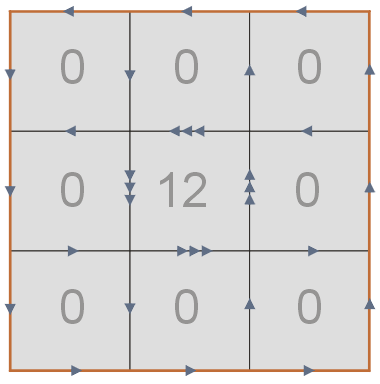

The model Gauss' theorem states that the sum of all the numbers in the boxes, 12, equals the sum of all the arrows on the perimeter of the region, also 12.

Example: Suppose that a vector field is described by the arrows shown in the picture. First, let's count the arrows entering and leaving each of the nine boxes to get the divergence values for the boxes (i.e. let's apply point 8 of the model). We get 12 for the center box and 0 for all the other boxes. Write these values in the boxes. (We could also use point 11 of the model to get these numbers, but that is not as easy.)

Now sum up the numbers in all of the boxes. We get 12. This is one side of Gauss' Theorem.

Now we count the arrows on the boundary of the region. We also get 12. This is the other side of Gauss' Theorem. The theorem says that these two numbers are always the same.

The model Gauss' theorem states that the sum of all the numbers in the boxes, 14, equals the sum of all the arrows on the perimeter of the region, 14.

Example: Suppose that a vector field is described by the arrows shown in the picture. Again, counting arrows entering and leaving each of the nine boxes gives the divergence values shown in the boxes.

The sum of the numbers in all of the boxes is 14. This is one side of Gauss' Theorem.

Counting the arrows on the boundary of the region also gives 14. This is the other side of Gauss' Theorem.

Stokes' Theorem

Stokes' Theorem states that the line integral of a vector field around any loop C is equal to the flux integral of its curl through any surface S enclosed by the loop.

|

|

(6) |

![]() is the unit normal to the surface S, and the direction of

is the unit normal to the surface S, and the direction of

![]() and the direction of C are related by the right-hand-rule.

For the theorem to hold, the field must be continuous with continuous derivatives

throughout R (i.e. continuously differentiable).

In two dimensions, Stokes' Theorem is equivalent to Green's theorem.

and the direction of C are related by the right-hand-rule.

For the theorem to hold, the field must be continuous with continuous derivatives

throughout R (i.e. continuously differentiable).

In two dimensions, Stokes' Theorem is equivalent to Green's theorem.

Derivation of Stokes' Theorem

Stokes’ theorem is derived by breaking up surface S into many small planar elements, writing down the curl definition equation for each of them, and summing them all up. One side of the resulting equation becomes a surface integral and the other side becomes a line integral around the boundary.

Suppose that we have a vector field F, and that in the field is an (open) surface S

with a boundary C. Now imagine dividing S into many tiny plane

surface elements. Suppose that there is a point P inside one of these elements,

and that the surface element has unit normal

![]() .

We saw previously that the component of the curl at P

in the direction

.

We saw previously that the component of the curl at P

in the direction

![]() is approximately equal to the line integral of F around the boundary CE of the

surface element, divided by the area ΔA of the surface element.

is approximately equal to the line integral of F around the boundary CE of the

surface element, divided by the area ΔA of the surface element.

The approximation becomes exact in the limit as the area of the surface element goes to zero. Now multiply both sides of the above equation by ΔA and sum up over all the elements that make up the surface S.

On the right side of this equation, the sum over all surface elements can be replaced by a sum over all the edges of the surface elements. Now notice that for any two adjacent elements the line integral from one element precisely cancels the line integral from the other element along their common edge. (Look at the adjacent loops in the picture.) Only the line integral along the exterior edges does not cancel. The result is that the right side of the equation reduces to a sum over just the exterior edges. In the limit as ΔA→0, the sum on the left side of the equation can be replaced by a surface integral over the entire surface and the sum on the right side becomes a line integral around the curve C. Thus the equation becomes

which is just Stokes’ theorem.

The line integrals can be evaluated indirectly by doing a surface integral instead, according to Stokes' Theorem.

Example: The picture shows the field F (x, y, z) = (−ωy, ωx, 0) and two closed paths in the z=0 plane: a circle with radius r and a 3×3 triangle. In a previous example we calculated the line integral of F around the circle and around the triangle. The result for the circle is 2ωπr2, and for the triangle it is 9ω.

Here we want to show that we can get the same result by doing a surface integral instead, and then invoking Stokes' Theorem. Stokes' theorem states that

Thus, instead of doing the line integral on the LHS we will do the surface integral on the RHS.

For this field we previously calculated that the curl

is 2ω![]() everywhere in the field. If the surfaces bounded by the circle and the triangle are chosen to

lie in the z=0 plane then they both have unit normal

everywhere in the field. If the surfaces bounded by the circle and the triangle are chosen to

lie in the z=0 plane then they both have unit normal

![]() =

=

![]() so the surface integrals reduce to

so the surface integrals reduce to

Since the area of the circle is πr2 and the area of the triangle is 9/2 we get the same answers as before.

A Model for Stokes' Theorem

This model will help us understand what Stokes' theorem means.

- The model is 2-dimensional.

- Break up the region R into a grid of ‘tiny’ square cells, each of size Δx = 1 by Δy = 1 (and thus area ΔA = 1), and each with a point at its center.

- Allow Fx and Fy (the components of field F), to take on integer values only. This implies that the circulation of F and the curl of F also take on integer values only.

- Because Stokes' Theorem is concerned with circulations (line integrals around closed loops), we need only look at the values of Fx on the top and bottom edges of a cell, and the values of Fy on the left and right edges.

- n arrows pointing to the right at an edge mean that Fx = n there. (Arrows pointing to the left mean that Fx is negative there.)

- Similarly, n arrows pointing up mean that Fy = n there. (Arrows pointing down mean that Fy is negative there.)

- Arrows pointing along an edge of a cell also indicate circulation. m arrows pointing counter-clockwise and n arrows pointing clockwise means that the circulation of that cell is m−n.

- The definition of curl in this model is that the curl at a point equals the number of arrows pointing counter-clockwise around a cell minus the number of arrows pointing clockwise. Write this number in the cell. Here are 3 examples where the circulation of a cell is 3 and hence the curl at the point in the cell is 3.

Three examples of cells where the circulation, and hence the curl, is 3.

- n more arrows pointing upward at the right edge than the left edge indicate that ΔFy /Δx = n.

- Similarly, n more arrows pointing to the right at the top edge than the bottom edge indicate that ΔFx /Δy = n.

- Taking ΔFy /Δx

and subtracting ΔFx /Δy

from points 9 and 10 is another (more complicated)

way to compute the curl.

For example, calculating the curl this way for the three examples above gives

(since the cells have size Δx=1 and Δy=1):

- ∇×F = ΔFy − ΔFx = (0−(−1)) − ((−1)−1) = 3

- ∇×F = ΔFy − ΔFx = (0−0) − ((−3)−0) = 3

- ∇×F = ΔFy − ΔFx = (2−(−2)) − ((−1)−(−2)) = 3

- Stokes' theorem in this model states that the sum of all the numbers in the cells (representing the surface integral of the curl on the surface) equals the sum of all the arrows on the perimeter of the region (representing the line integral around its boundary).

The model Stokes' theorem states that the sum of all the numbers in the cells, 12, equals the sum of all the arrows on the perimeter of the region, also 12.

Example: Suppose that a vector field is described by the arrows shown in the picture. First, let's count the arrows going counterclockwise and clockwise around each of the nine cells to get the curl values for the cells (i.e. let's apply point 8 of the model). We get 12 for the center cell and 0 for all the other cells. Write these values in the cells. (We could also use point 11 of the model to get these numbers, but that is not as easy.)

Now sum up the numbers in all of the cells. We get 12. This is one side of Stokes' Theorem.

Now we count the arrows on the boundary of the region. We also get 12. This is the other side of Stokes' Theorem. The theorem says that these two numbers are always the same.

The model Stokes' theorem states that the sum of all the numbers in the cells, 14, equals the sum of all the arrows on the perimeter of the region, 14.

Example: Suppose that a vector field is described by the arrows shown in the picture. Again, counting arrows going counterclockwise and clockwise around each of the nine cells gives the curl values shown in the cells.

The sum of the curl values in all of the boxes is 14. This is one side of Stokes' Theorem.

Counting the arrows on the boundary of the region also gives 14. This is the other side of Stokes' Theorem.

If you would like to leave a comment or ask a question please send me an email!